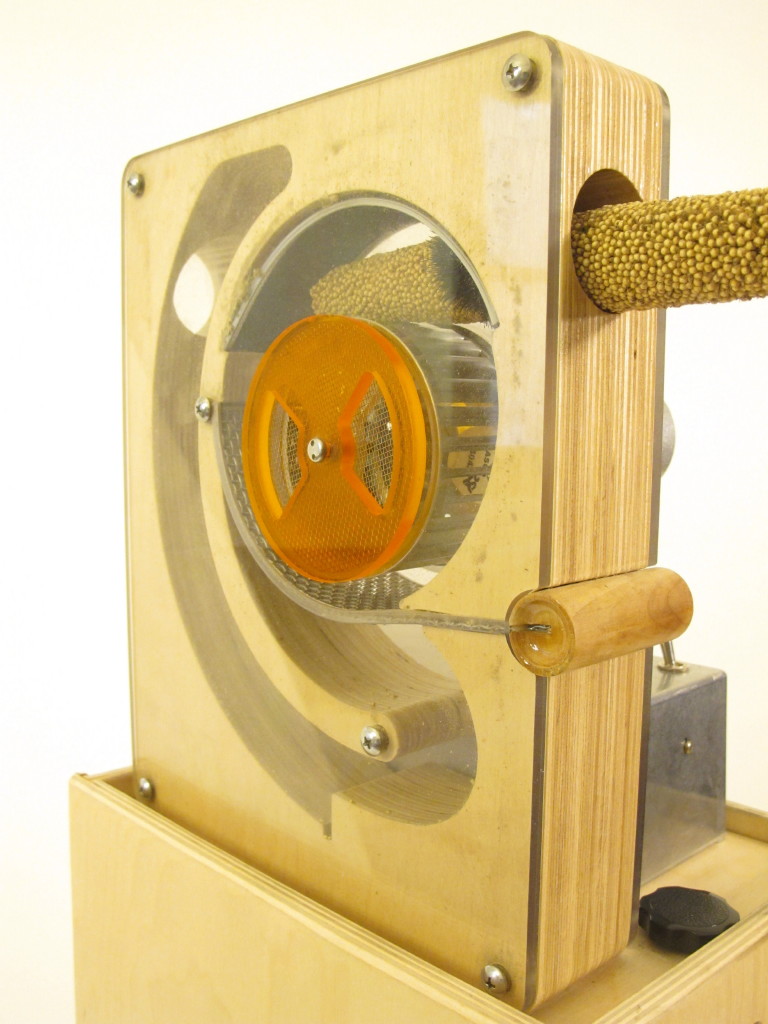

We have a new prototype that we are eager to test in Niger. We believe our latest prototype resolves the issue of clogging and output speed. Still solar powered, it is a simpler and more compact machine lower energy consumption than the AF2 (the prototype we tested in Niger in 2015). The “crop engagement element” consists of two sets of rotating v-shaped wire flails, which the panicle goes in between. This eliminates the need to rotate the panicle and takes the grain off much faster than in any previous prototypes.

“Crop Engagement Element” for thresher prototype October 2016. A pair of flails contacts the entire panicle surface as it passes through.

The grain and florets are knocked into a chamber, where secondary threshing occurs. The grain drops out of the bottom, and any chafe is ejected out the top. We see opportunities to incorporate decortication into the process as well as making the machine also effective on sorghum.

Project Background

Since 2006, a team of designers based at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts have worked to develop an affordable and labor-saving pearl millet thresher that complements existing social and cultural dynamics of the people who use it. Over these past years, numerous individuals and organizations have provided ideas, financial and technical support, and help with field testing.

Women in Niger trying out the solar powered AF2.

The crop and its challenges

Pearl millet is is a highly nutritious staple cereal, produced on small farms by millions of people in sub-Saharan Africa. The plant requires no irrigation and can grow in the harshest conditions.

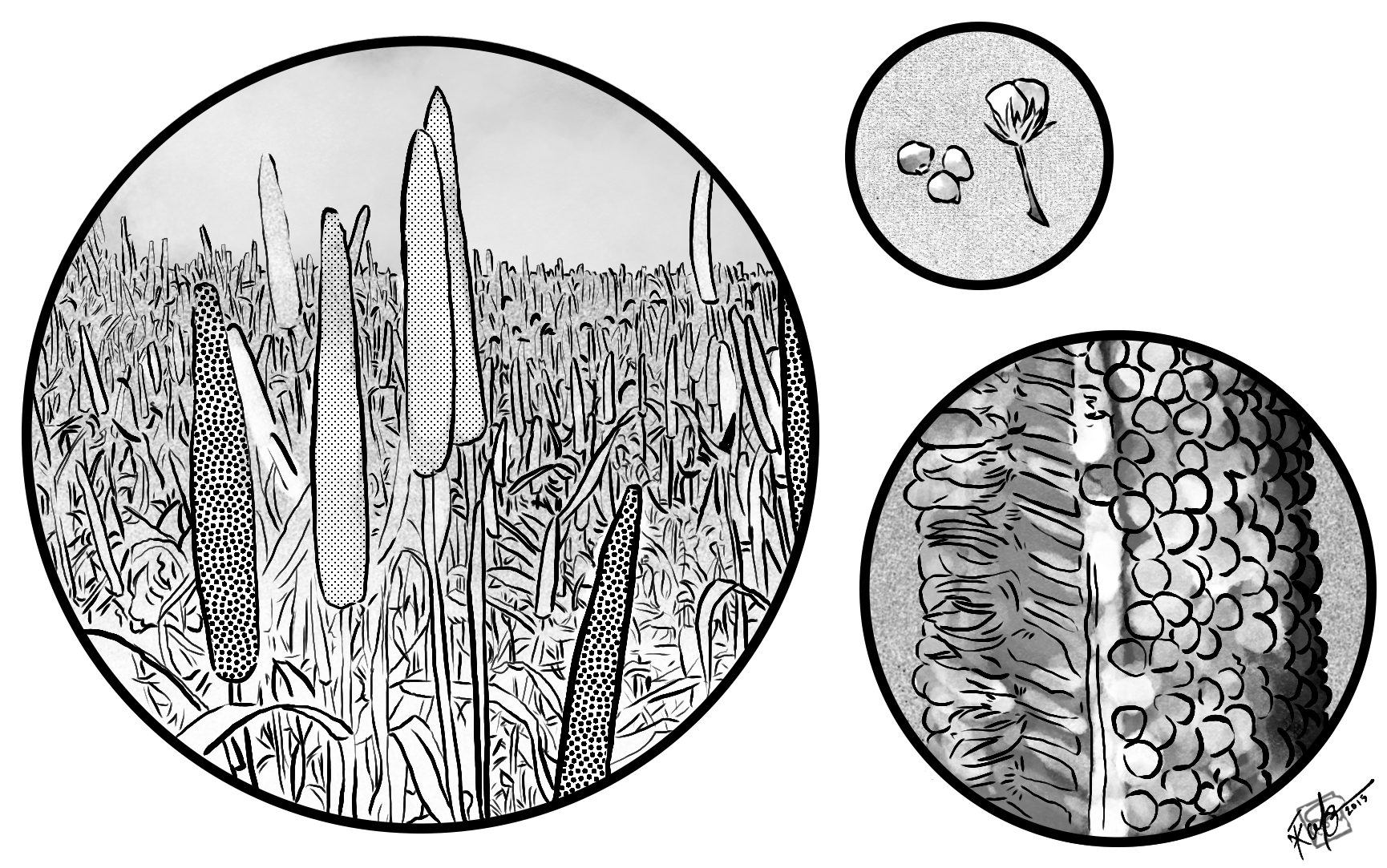

But threshing and separating the edible grains from the panicle is a slow and labor-intensive process. Practices vary by region and ethnicity of the farmers, but in general women do the work of extracting the grain by hand, with repeated cycles of pounding and winnowing. The photo at left was taken in Niger.

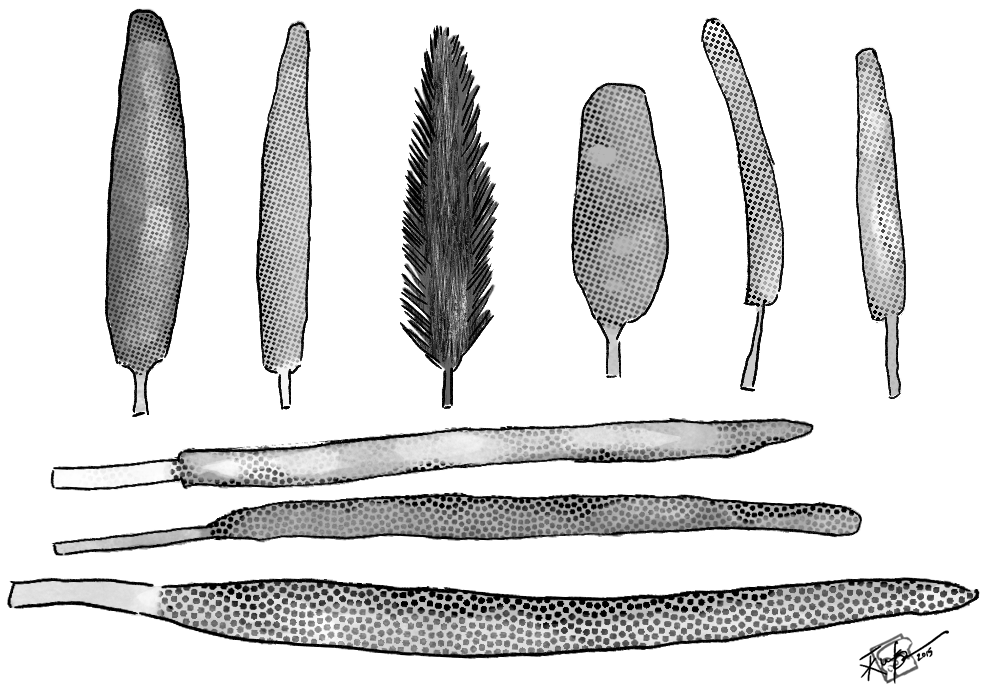

Pearl millet comes on a stalk called a panicle. On the panicle, seeds are held in place by a glume – a group of tentacles holding the seed in place. The seeds, in their glumes, are held in groups of three. These groups are called florets.

With a grain like wheat, you can just shake the stalk and the grain falls off. With pearl millet, the whole floret falls off. You either need to rub or strike the panicle to knock the seed out. It’s different from most other grains in that way: it just doesn’t come off easily.

An additional challenge of this project is that pearl millet varies widely in its shape and physical behavior based on land race and growing conditions. For example, Namibian pearl millet panicles are much thicker than those available for experimentation in Massachusetts, and Nigerian panicles are much longer.

When the time and energy cost of threshing and winnowing the millet is reduced, it also reduces the health burdens and stress placed on the women responsible for the task. We aim to make a thresher with a low cost and simple design, in order to make a universal improvement to the processing of an important and nutritious crop that has the potential to improve global food security.

Our Thresher

Our style of thresher, which we call “Pearl Millet High-Impact Thresher (pm HIT),” uses sharp force to remove just the edible grains from the stalk, while leaving the rest of the panicle intact. This largely eliminates the need to winnow and produces clean unbroken grain.

The current prototype of our thresher, pictured here, is called the Ant Farm. It uses a fan inside a specially shaped wood-and-plexiglass case to knock the millet off the panicle and deposit it into a receptacle beneath the thresher.