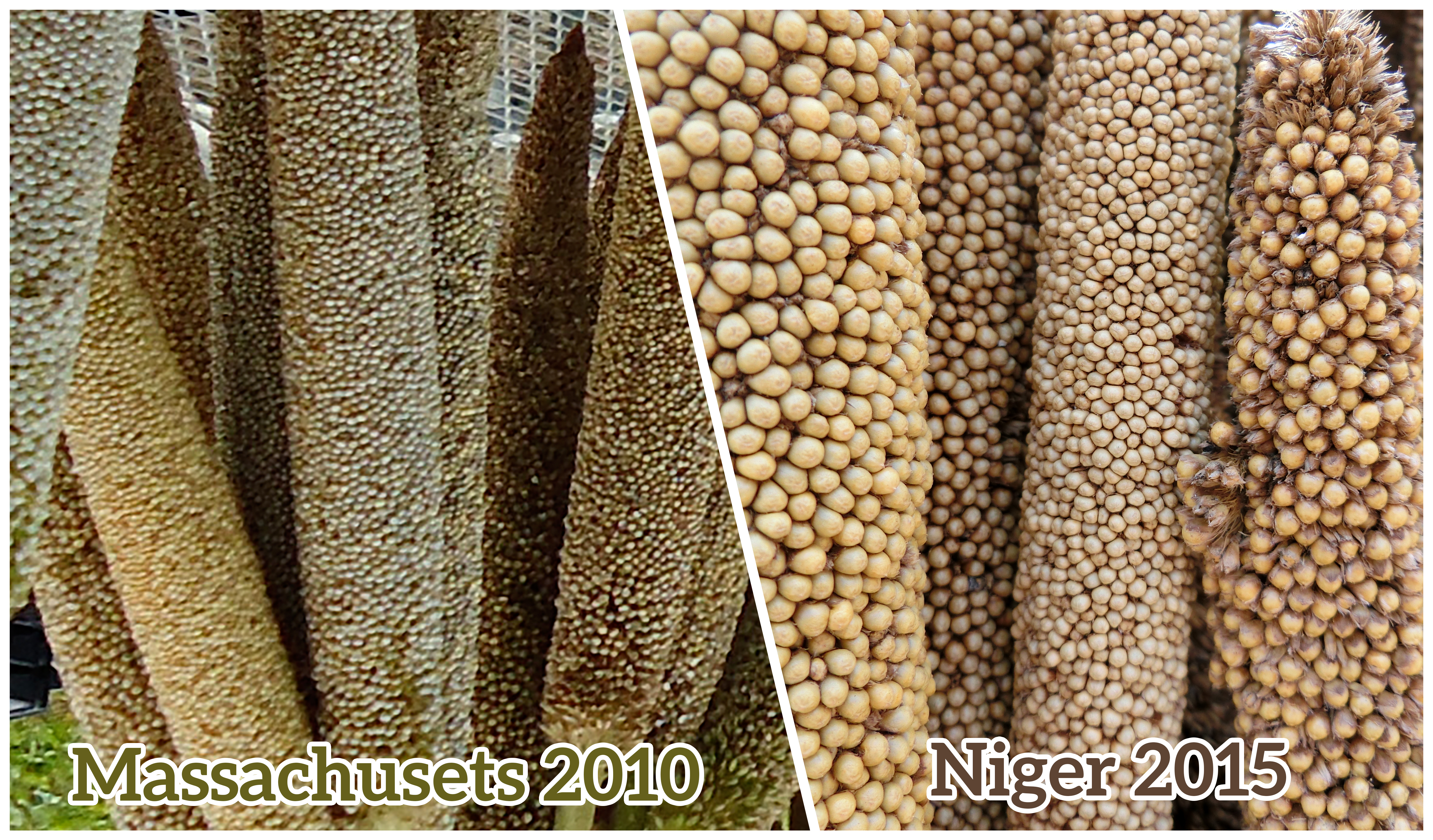

We learned from the 2014 trip to Niger that the threshers we’d built so far were inadequate for their pearl millet. There was significantly more variation in the panicles than there was in the millet we used for testing in Massachusetts.

Left: The pearl millet grown on campus at Hampshire College was extremely uniform, allowing for more predictable threshing. Right: The panicles in Namibia and Niger are much more varied, and often break apart more easily.

We realized that we needed to incorporate some amount of winnowing into the process, so that the thresher would produce clean grain.

The Ant Farm 1 was our prototype for solving that problem.

The Pearl Millet High Impact Thresher: Ant Farm 1, the first working prototype of our current design approach to the thresher.

This design was one of our many attempts to create a secondary friction action: By using the fan as both a hit surface and a fan, we were able to put more kinds of impact into the process. This helped separate the millet from its florets even when the florets were dislodged from the panicle. The screen under the fan then prevents the millet from passing through until it has been knocked loose from the floret.

We knew this configuration could be hand cranked, but to make the testing process easier we decided to motorize it. After making that switch, we decided it would be worthwhile to build the device primarily to use a motor.

We built on this design to bring to Namibia for field testing. In Namibia people generally thresh their whole crop at once, so going in we knew it wasn’t going to be an ideal solution for their approach to threshing. But it was an opportunity to test it with a bunch of pearl millet that was closer to the kind found in Niger.

We saw that testers weren’t using a fully charged battery, so the thresher didn’t work as well as it did in the shop. This was one of the significant lessons we took away from the Namibia trip, and building on it we decided to use solar panels for the next iteration: the Ant Farm 2 can be plugged in, but its main power source is solar, so it never needs to be recharged.

One of the interesting things we found in Namibia was the business model that had emerged for threshing. A businesswoman had invested in a $6,000 diesel thresher that could be pulled by a car, and she would hire it out to the different farms and thresh their season’s crop in a very short period of time: a matter of minutes rather than hours. The only complaint was that people had to wait for her services.

This business model is applicable in some situations but is not feasible for very poor farmers, and is incompatible with the approach in Niger of storing millet on the panicle and threshing it daily as needed.

A diesel thresher used to thresh the entire year’s crop in Okathitu, Namibia. Photo by Aaron Wieler.

The speed of our thresher emerged as a concern in that context. In Namibia, where the people had access to a diesel thresher, the speed of the Ant Farm was completely unacceptable. But in Niger they thresh small quantities on a daily basis, so the Ant Farm only has to compete with manual threshing, not a large-scale thresher.

- Aaron Wieler’s notes from his 2015 trip to Namibia.